In competitive decision-making environments, every choice is shaped by the anticipation of an opponent’s response. This is the essence of zero-sum games, where one player’s gain is another’s loss. From classic board games like chess to modern AI-driven strategy systems, evaluating all possible moves quickly becomes computationally expensive. Minimax search offers a structured way to reason through these possibilities, but its brute-force approach can be inefficient. Alpha–beta pruning refines minimax by eliminating branches of the game tree that cannot affect the final decision, making intelligent play feasible even in complex scenarios.

Minimax Search in Zero-Sum Games

Minimax search models a game as a tree of decisions. Each node represents a game state, and each edge represents a possible move. The algorithm assumes that one player aims to maximise the outcome while the opponent aims to minimise it. By exploring the tree, minimax assigns a value to each possible move based on the best achievable outcome assuming optimal play from both sides.

While this approach is conceptually simple and theoretically sound, it faces a practical challenge. The number of possible game states grows exponentially with depth. Even for moderately complex games, evaluating every branch becomes infeasible. This limitation led to the development of pruning techniques that preserve optimality while reducing unnecessary computation.

Understanding Alpha–Beta Pruning

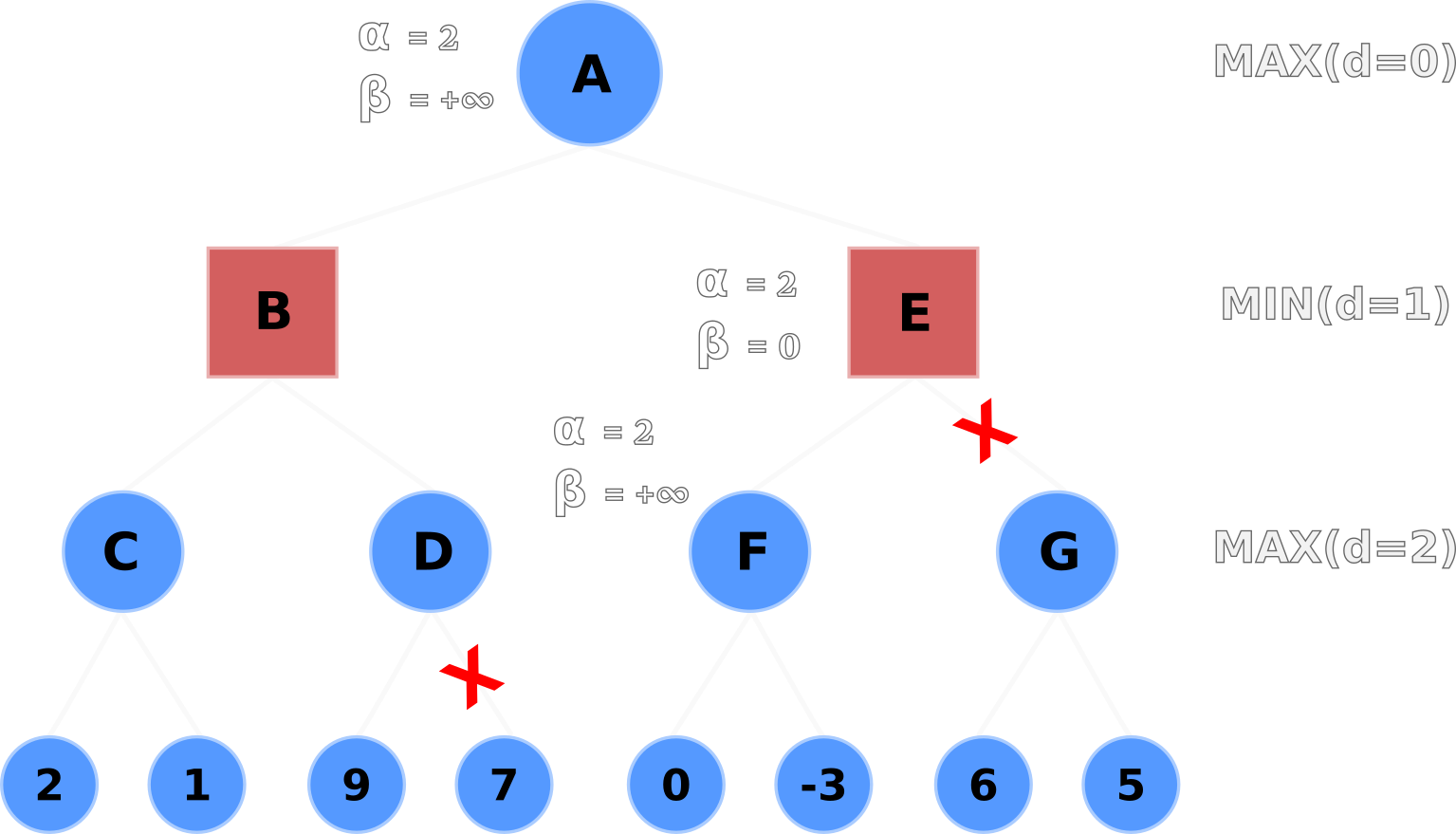

Alpha–beta pruning enhances minimax by introducing two bounds, alpha and beta, that represent the best already-known options for the maximising and minimising players. Alpha tracks the highest value that the maximising player can guarantee so far. Beta tracks the lowest value that the minimising player can enforce.

As the search progresses, these bounds are updated. When the algorithm discovers that a branch cannot produce a better outcome than an already examined alternative, it stops exploring that branch. This is pruning. Importantly, pruning does not change the final decision. It only avoids evaluating positions that are irrelevant to the optimal outcome.

This efficiency gain can be dramatic. In ideal conditions, alpha–beta pruning can reduce the effective branching factor significantly, allowing deeper searches within the same computational budget.

How Alpha–Beta Pruning Eliminates Irrelevant Branches

To understand pruning intuitively, consider a maximising player evaluating a move that already guarantees a strong outcome. If, during exploration, the minimising player finds a response that leads to a worse result than an alternative already available, there is no reason to continue evaluating that path. The minimising player would never choose it.

This logic applies symmetrically for both players. By comparing partial results against alpha and beta bounds, the algorithm identifies branches that cannot influence the final decision. These branches are skipped entirely.

The effectiveness of pruning depends on the order in which moves are evaluated. Good move ordering leads to earlier pruning and greater efficiency. This insight has influenced the design of many modern game-playing systems and search-based AI applications.

Practical Importance in AI Systems

Alpha–beta pruning is more than a theoretical optimisation. It is a foundational technique in artificial intelligence, especially in adversarial search problems. It enables real-time decision making in environments where exhaustive search is impossible.

Beyond games, the principles behind pruning influence optimisation problems, planning systems, and strategic simulations. By focusing computation on meaningful alternatives, AI systems can allocate resources more intelligently. Learners exploring these concepts in depth often encounter alpha–beta pruning as a milestone topic in advanced study paths such as an ai course in mumbai, where game theory and search algorithms intersect with practical AI design.

Limitations and Enhancements

Despite its strengths, alpha–beta pruning has limitations. Its performance is highly sensitive to move ordering. Poor ordering can significantly reduce pruning effectiveness, making the algorithm closer to plain minimax in cost.

To address this, enhancements such as heuristic evaluation functions, iterative deepening, and transposition tables are commonly used. These techniques work together to guide the search toward promising moves early, increasing pruning opportunities. In practice, alpha–beta pruning is rarely used in isolation. It is part of a broader toolkit for efficient search and decision making.

Understanding these trade-offs helps practitioners apply the technique appropriately rather than expecting it to solve all scalability challenges on its own.

Relevance for Modern AI Learning

Alpha–beta pruning remains relevant even as machine learning and reinforcement learning gain prominence. It represents a class of symbolic AI techniques that emphasise reasoning, guarantees, and interpretability. For students and professionals building a strong theoretical foundation, exposure to such algorithms provides a valuable perspective on how intelligent behaviour can emerge from structured search rather than data-driven learning alone. This balance is often highlighted in curricula such as an ai course in mumbai, where classical AI methods complement modern approaches.

Conclusion

Alpha–beta pruning transforms minimax search from an elegant but impractical idea into an efficient decision-making tool for zero-sum games. By eliminating branches that cannot influence the final outcome, it preserves optimality while dramatically reducing computational effort. Its principles continue to shape AI systems that rely on strategic reasoning and adversarial planning. Understanding alpha–beta pruning not only deepens appreciation of game theory but also strengthens one’s grasp of efficient problem-solving in artificial intelligence.